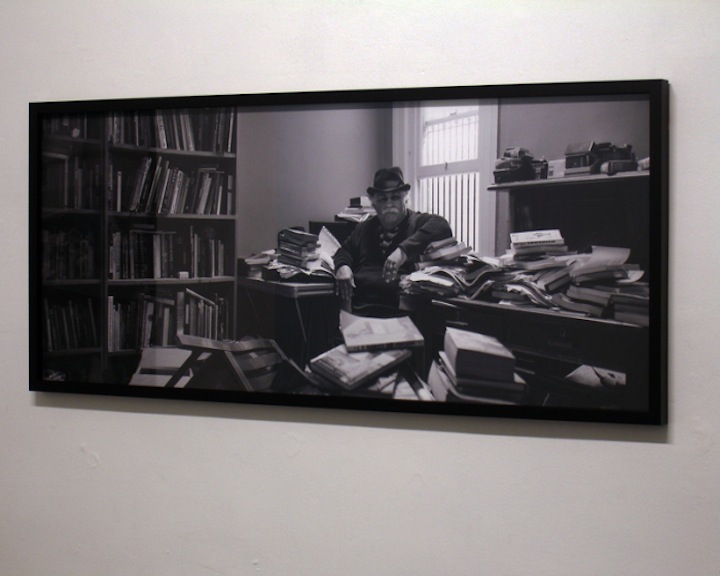

Lichtenberg

Mixed-media installation

Ghost World (catalogue essage for ‘Insomnia’)

‘Until you have wasted time in a city, you cannot pretend to know it well.’

–Julian Green, Paris, 1983

It kept looking at me. This owl perched on the window still. It was night. And I was in my cot as a toddler looking back at it through the bars of the cot’s wall. Unless I am mistaken this is the first memory I have of my childhood in Wauchope in 1947. Was this Hegel’s owl paying me a visit to remind me that only at dusk time our visible world is perhaps knowable but to a few amongst us ? The owl’s orange piercing eyes were silently dilating just like the owl in the early scenes of Bladerunner. I can also recall hands (very fleetingly) approaching me – I suspect it was my father’s – to pick me up and reassure me that our nocturnal visitor was quite harmless. Ten years later, I witnessed the catastrophic spectacle of my mother receiving the news by telephone that my father had passed away from leukaemia. My poor mother ran screaming hysterically onto the road outside our Tempe milk bar and collapsed into a heap reminiscent of Andre Masson’s calligraphic ink soldiers massacring each other. So much for my Wellesian two-bob Freudianism!

For after all, it was only an owl and in Greek (characteristically) it signified a pun: yes, besides being a symbol for wisdom, the Greek word for owl, also meant a dope. A boofhead. How can this be so? Ah, welcome to my lifeworld as an artist and a scholar: double-binds academic, cultural, existential and linguistic – have been plentiful throughout my life. Being a diasporic being 24/7 is like being caught in a turnstile door, engaged in what Hugh Kenner once described Buster Keaton’s oeuvre, as an ‘art of sinking.’ Or, if you prefer whilst we are talking of Keaton, let us cite here Robert Benayoun’s wonderful description of old stone face himself as ‘a Columbus sailing for Prague.’ You get the picture. Whether it is the academy – or for what passes for one in this country – or the art world – or for both, for insomniacs like me, it is a zero-sum game all round. You just can’t have your cake and eat it too. You just keep on sinking, never arriving, doing what you must do and hoping that you are making some kind of sense to yourself and others of this one shared turning world of ours.

Stop whingeing you might say, but believe me stuck inside that confounded turnstile of life, you start to having a fascination for the doomed figures of film noir – soul mates, to be sure, waiting for the dawn to arrive in Los Angeles, that city in our popular cultural imaginary that W. H. Auden once called ‘the great wrong place.’ Over the years you learn to live with insomnia. What else can you do? And as someone who incessantly reads, writes and produces images, your insomnia is of a particular kind: it is the kind that Maurice Blanchot speaks of, an insomnia, during the day as well as the night. You are forever awake, like life’s ebbing nocturnal tide. Life x-rayed. Insomnia as ‘percussive stillness’ (Blanchot).

I suspect my insomnia emanated from my unbridled cinephilia in the sixties and early seventies. And spending the wee hours as a fringe Push character seated in the crammed Caligaresque decor of the Piccolo coffee shop at Kings Cross. A locale worthy of a German Expressionist painting or play with a cast of unlikely characters – writers, artists, filmmakers, hustlers, blue and white collar workers, etc., sipping their coffees, talking about art, cinema, literature, philosophy and politics, smoking, playing chess and backgammon. With a jukebox to keep us company. And true to what certain philosophers have said of insomnia one’s consciousness would be stripped bare – 24/7 – by oneself. Disembodied, disinterested thought inescapably suggesting an ‘impossibility of hiding in

oneself.’(Emmanuel Levinas). It represents for this philosopher an unabated vigilance for the injustice and horror of the world. Insomnia, for Friedrich Nietzsche, was to be welcomed as ‘wakefulness itself.’ How many of us sail through life as one of Herman Broch’s ’sleepwalkers’. Dead to ourselves and to the world itself.

Whatever the city one finds oneself in – Paris, Sydney, New York or whatever – as insomniac one has their acute lucid moments as well as their weary exhausted ones. That is guaranteed. Melancholia will seep into your life as a constant companion. Depression too. That too is a certainty. And your body will start groaning, coming apart, coming to a stop fitting of Samuel Beckett’s characters. Also, insomnia breeds self-grandeur, so I am told. (Whew that was close!)

And like Emil Cioran you too, as insomniac, may vouch for walking ‘the streets like some kind of phantom. All that I have written much later has been worked out during those nights.’ It is strange, that for me and several of my Push friends, we use to kiddingly describe ourselves after the famous comic book character, that how we saw the world then as spectral figures negotiating our unfilled emancipation in the sixties. Not that things are radically different these days. The insomnia is still with me but now, as Jonathan Crary as argued in his new sharp nuanced polemic 24/7 Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (2013), with the ever-encompassing digital world of ours I have the unmistakable feeling that there are more of us now than before who are tossing and turning in our beds.

John Conomos, July 2013